Starting in July of this year, my family and I began the process to relocate from the east coast to the west coast for new digs and work at thoughtbot San Francisco. After living in New York City for a decade, this wasn’t a decision taken lightly but I also didn’t know then just how complicated the process would end up being.

There are a lot of things that I could talk about it but in this first part, we’re going to focus on how we made the decision for our mode of travel using design thinking, and for the second part, we’ll jump into two of the specific challenges we encountered along the way.

The last time I went through a big move like this, it was from Austin to Brooklyn - half the distance - with my then fiancé. I’d accepted a job in downtown Brooklyn and we slept on an air mattress in one of my best friend’s extra bedrooms on the border of Park Slope and Gowanus - ask me about the busted seam in the middle of the night… whew! And while it didn’t feel like it at the time, I now realize how different the stakes were then.

Fast forward to now and the move was double the distance with my wife and a young kid and 10 years of life in New York City — a much taller order. Everyone caught up? Yes? Okay, let’s get a move on.

From point A to point B

After some light investigation, we decided that the bulk of our stuff would be best moved using PODS — we’d get a 8’ by 8’ or 16’ by 8’ cargo container that would get shipped to a facility in Queens for a quick overnight before landing in a climate controlled Oakland storage center until we scheduled final delivery wherever (and whenever) we found a place to live in San Francisco.

That was our stuff, okay. So how do we approach physically getting to the Bay Area? That was the question my wife and I needed to answer. We had six weeks — our time ‘budget’ — to work with for the trip and were ready to start crafting our approach. Taking inspiration from the double diamond model I often use in my work as a designer, we began working through options with a flare and focus approach.

Launched in 2004 by the UK Design Council, the double diamond model is a non-linear way of illustrating the iterative design process to designers and non-designers alike with:

- Divergent thinking — thinking broadly, keeping an open mind, considering anything and everything

- Convergent thinking — thinking narrowly, bringing back focus and identifying one or two key problems and solutions

Empathize: the first mode

And by first, I mean the place where we started because this process isn’t always sequential — nor do we need to follow any specific order because segments can often occur in parallel and you can repeat them iteratively as needed. So, this “first mode” — often called discover (or empathize, as I’m calling it here) — is where my wife and I started.

Even though I know my wife pretty well, I wanted to understand what she wanted out of this trip. And vice versa. As a result, we started wide, thinking broadly. And we took a 15 minute break from packing boxes to fill out as many post-its as we could.

And this is how 15 minutes turned into 45 minutes and a few discussions over several nights.

Our takeaways included:

- Wanted to make the most of our time, however we travelled (read: wanted to not drag it out)

- Wanted a break between our lives in New York City and our new life in San Francisco — not a vacation exactly but some substantial time off

- Needed to be able to carry a few things — two to three suitcases — that we’d need upon arrival in the Bay Area until we secured a non-temporary place to live

- Wanted to see parts of the country one or both of us hadn’t seen (read: adventure!)

- Wanted to be invigorated by our travel

- Needed to be in San Francisco by second week of August

- What about the dog?

So with all of that in mind, we dug into our options.

Define: the second mode

If this were a traditional design thinking process, we would’ve built several point-of-view statements (read: a meaningful and actionable problem statement), which would allow ideation in a goal-oriented manner. In our situation, that was a bit overkill. But we should follow the construct entirely, see this through.

Often a POV statement is structured something like this:

[One or more humans and maybe a pup] needs [verb] because [compelling insight].

So, for our purposes, it would look something like:

We are a family who needs to get from New York City to San Francisco because I found a new job.

Typically, a number of POV statements are built during a design thinking process but for our purposes, we’ll stick with our single statement.

The same goes for “How Might We” (HMW) questions, which typically fall out of POV statement(s) or other design principles. And even though we knew our path forward — we’d posed plenty of HMW questions in deciding to leave New York City — but for the sake of exercise complete-ism, let’s say this is our statement:

How might we get ourselves and some small amount of stuff from the east coast to the west coast in less than six weeks?

And the same goes for the HMW questions as the POV statements, typically you’d make a bunch of them, either by reframing different contextual informations or applying the five whys (or, 5 whys), a simple problem-solving exercise designed to get to the heart of any problem.

Easy, right? Right.

Ideate: the third mode

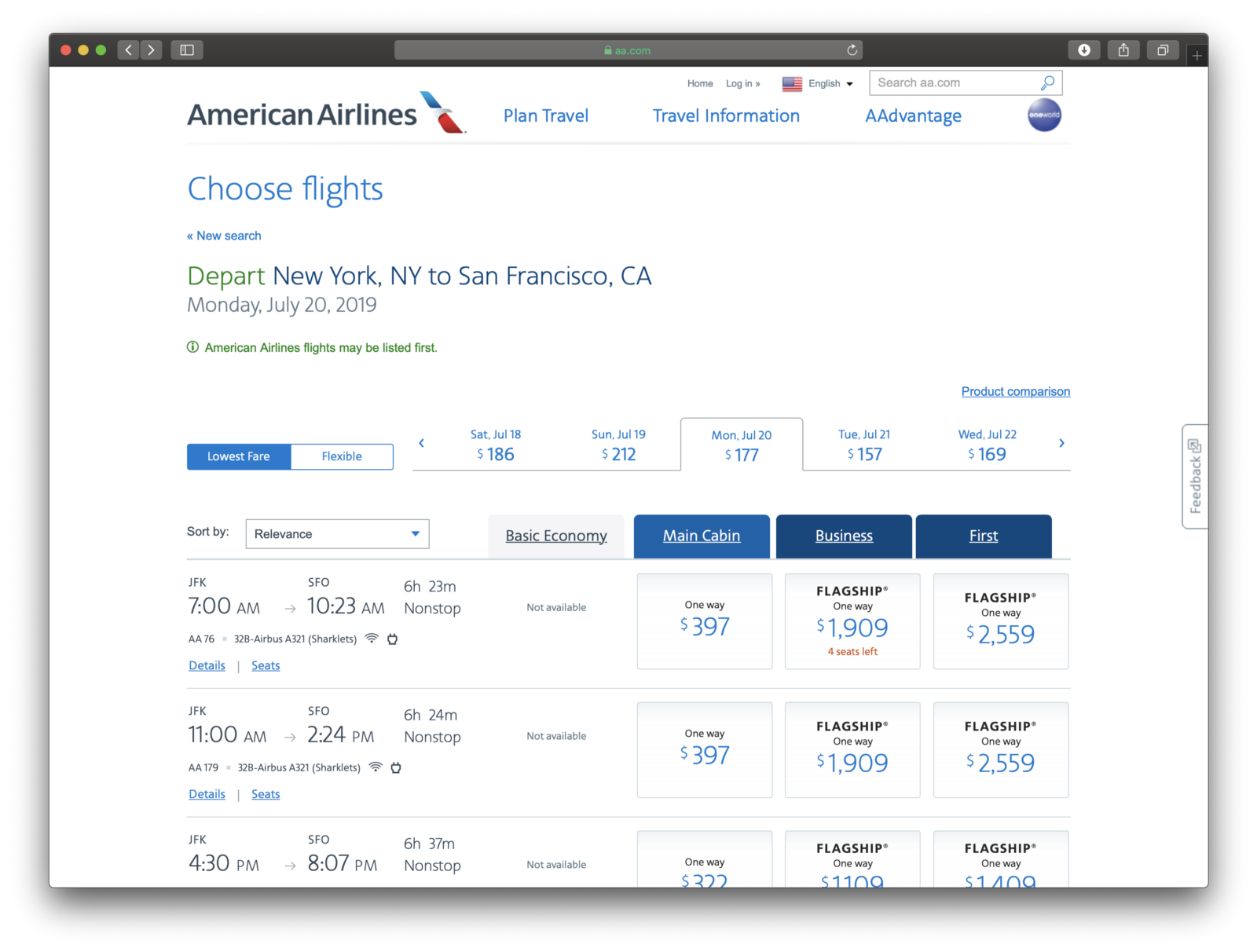

So, let’s get into all the different ways we could travel in such a way that we’d get there in a way that would fit our constraints. Flying, to be sure, was an option.

A good price but that wasn’t much space or time between the thread of our NY lives to our new California existence. And there’s a pretty small amount of cargo that we can carry. No, thank you.

And so we looked at taking a train cross-country.

A train from New York to Washington, D.C. to Chicago to Los Angeles to Oakland and a bus from there to San Francisco in 84 hours definitely gave us space and time but we had a fair amount of luggage and stuff that we needed to access while we found a permanent place to live. Not much space allocated to you with a train ticket. So, while riding the rails would be pretty hands-off and cool, that option was out.

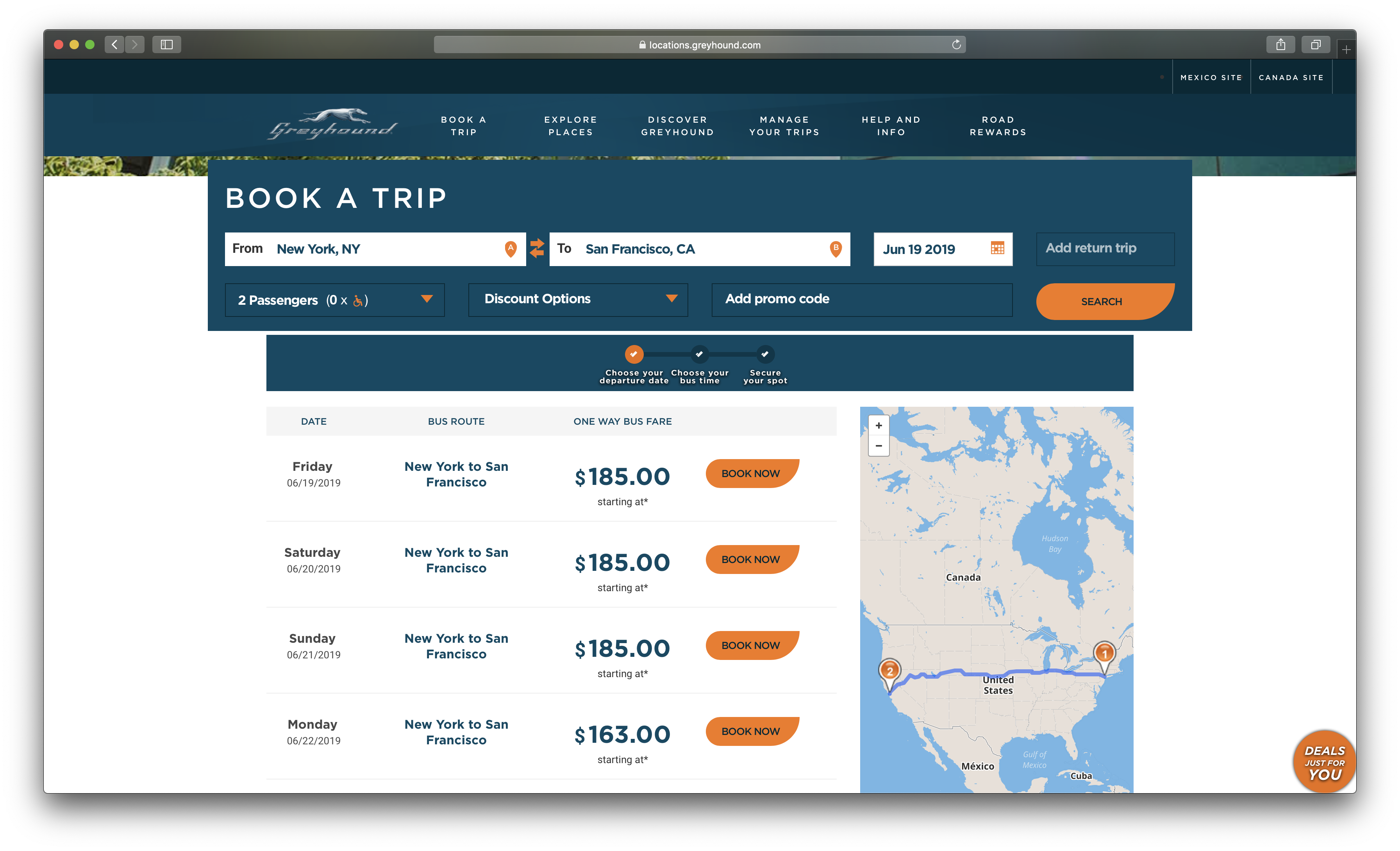

What about taking a bus?

The bus option was well-priced but some of the same paradigm as a train, it would take over four days and we wouldn’t be able to bring the amount of stuff that we thought we’d need when we first landed in San Francisco.

Walking? Is that an option?

It would take us 80 days, if we walked 12 hours everyday. That would blow our time “budget”, that wouldn’t get us there fast enough. Plus the wear and tear with a five-year-old and a number of suitcases and boxes doing this trip in July, yeah right. Absolutely out of the question.

And so, this is how we decided that we — read: not road trip people — decided to take a road trip over flying over cross-country train over bus over walking, a road trip that according to Google Maps should take about 45 hours to cover 2,992 miles. Yeah — 2,992 miles, 4,815 km, 45 hours. Yeah. Besides, we asked ourselves, when would we have the chance to do a road trip across the country that could take two-ish weeks in a car with a small child?

In case you’re wondering about what we did with our pup in all of this, we used a pet relocation service to transport her from one coast to the other. So much easier and one less creature to think about along the way.

Design thinking isn’t an exact science. And your mileage may vary but it’s helpful is tackling all sorts of problems, business ones and home ones too.

So, that’s the general how. In the second part of this article, we’ll get into the nitty gritty of two specific challenges we encountered along the way.

Thanks for reading.