Hi hello, friend. Glad you’re here. I just led my very first remote design sprint. And I’d like to add to the growing pile of suggestions in the hopes that you, dear reader, will find it helpful.

It’s important to note this post wasn’t written inside a vacuum. Though the tenets and tips below are (I hope) not ephemeral ideas, the impetus was driven from the state of the current state of the world.

We are in the middle of a pandemic.

We are in the middle of social upheaval and calls for change in response to centuries of the exclusion, abuse, and murder of the Black community.

The US specifically is in the middle of a political crisis where our police are becoming even more militarized and brutal and where underpaid teachers are being sent back to schools to teach children with no regard to anyone’s health or safety, among many many other troubling things.

Recognize with your team that this is happening. Talk about it. Many of your team members, including yourself, are probably compartmentalizing some complex and difficult emotions just to get through the day. Be kind and give folx breaks. Give yourself a break. Know that although this sprint may need to happen, it is certainly not a priority.

Given that you are reading this and perhaps need to facilitate one, know that the only strategy you really need to employ is being a good human and being good to other humans. That’s it. That’s the post.

But for those looking for a few concrete ideas to help improve their sprint process, particularly in a remote setting, the following tips are for you.

Flexibility is key

Design sprints, while incredibly effective in a short amount of time, can be mentally draining. It’s a lot to ask of people to do all-day problem-solving activities for an entire week. Acknowledge that fact with your team. Thank them for their time. And note that some folx may be responsible for their normal day-to-day work on top of this. Encourage your team to be flexible with the schedule and work at a sustainable pace.

As a facilitator, you can help support your team by writing out an agenda for the day and describing which parts are group activities and which ones are more indivualized. Your agenda should have a clear stopping time. Try and respect that time. Some activities may take longer than anticipated (and that’s okay!) — see if subsequent activities can be shortened or pushed to the next day.

Additionally, be mindful that not everyone on your team has the privilege of a quiet workspace at home. Normalize interruptions and let folx know to pop out when they need. Say hello to the 6-year-old wandering into the video frame. Squee excessively over pets; pets are nearly always worth an interruption.

Take breaks (lots of them)

Are you a person that is invigorated by a whole week of full-day meetings? I admire your energy. I fully support your lively attitude while I slowly sink lower into my chair, staring blankly, debating in my head whether hotdogs really are sandwiches.

Many people need rest to restore their mental battery. Burnout is amplified even more when you’re staring at a screen. Make time for breaks, perhaps more than you normally would in-person, including meals.

Lunchtime, at least at thoughtbot, has always been a social activity for the team during a sprint. In a remote setting, it’s a welcome opportunity for everyone to turn off their laptops and recharge their minds a bit. As an added bonus, chatting about what folx managed to cobble together from the depths of their fridge is a built-in icebreaker conversation.

Turn off webcams (sometimes)

The Buggles have never been more right than they are today: video really did kill the radio star. For many teams, days are packed with Zoom meetings, a Brady Brunch-esque grid of faces meant to replace our long-table meeting rooms. In theory, it’s a good substitute, but in practice, it can often lead to screen fatigue. Sprints are no exception.

I’m not against video conferencing. I use it often and I think it’s important for a sprint team to have discussions with faces in view. That said, we found it helpful to ask folx to disable their video for certain activities, using audio only. The team was able to place more focus on our remote whiteboard (we used Miro).

It’s worth mentioning, you should discuss this with your team beforehand (directly and/or privately) to verify this is an approach that works for all. Not everyone is able to communicate effectively without video available. And there are also many situations in which someone may not want to turn on their webcam at all during a meeting. Be flexible, be supportive.

Let’s recap!

A hallmark of a sprint — as opposed to other, less cool meetings — are walls filled to the brim with sticky notes, whiteboards marked with unexplainable squiggles, and drawings taped up in what little space is left. It’s a lot to take in. But it’s also a great visual of all the information you’ve captured so far and when. And it’s a reference point for what your team will ultimately be building.

An in-person facilitator uses this room full of artifacts as a tool to guide the team. It’s easy to remind everyone of what you discussed or decided on the day before by walking over and pointing at it. This is an effective way to show the team how each activity builds on one another to ultimately create your final prototype for testing.

In a remote setting, you can recap these important decisions by using the attention management tool in Miro.

Analog can still work

Not every sprint activity needs to be translated to a digital space. One such activity is Speedy Eights. The main point of this exercise is to churn out as many small interactions in the form of wireframes as quickly as possible without getting too detailed. This activity (and most of the Diverge Day activities) is a way for each individual to generate ideas that they may or may not use in their final storyboard. Paper and markers still work well — just let your team know ahead of time to have these supplies handy. The back of a phone bill and the half-broken crayon you found under the couch can also work in a pinch.

The individual storyboarding exercise can also still be on paper. Have participants take a picture of it when finished and upload it to the remote whiteboard in preparation for group critique and voting.

Digital drawing tools are a plus

There comes a time in every designer’s life where you have to draw in front of your non-designer team and then explain to them that you’re a designer, not an illustrator, but you still went to art school so you really have no excuse, but at any rate here’s a very poor drawing of a hand holding a phone. This very event is inevitable during a sprint. We call it storyboarding.

Re-creating the final storyboard activity is awkward at best if your only tool is your laptop trackpad (it’s doable, but not ideal). If you have the luxury of owning a a tablet with a stylus, you’ll probably have an easier time when drawing. Be sure to test out your tools ahead of time with whichever digital whiteboard you’re using.

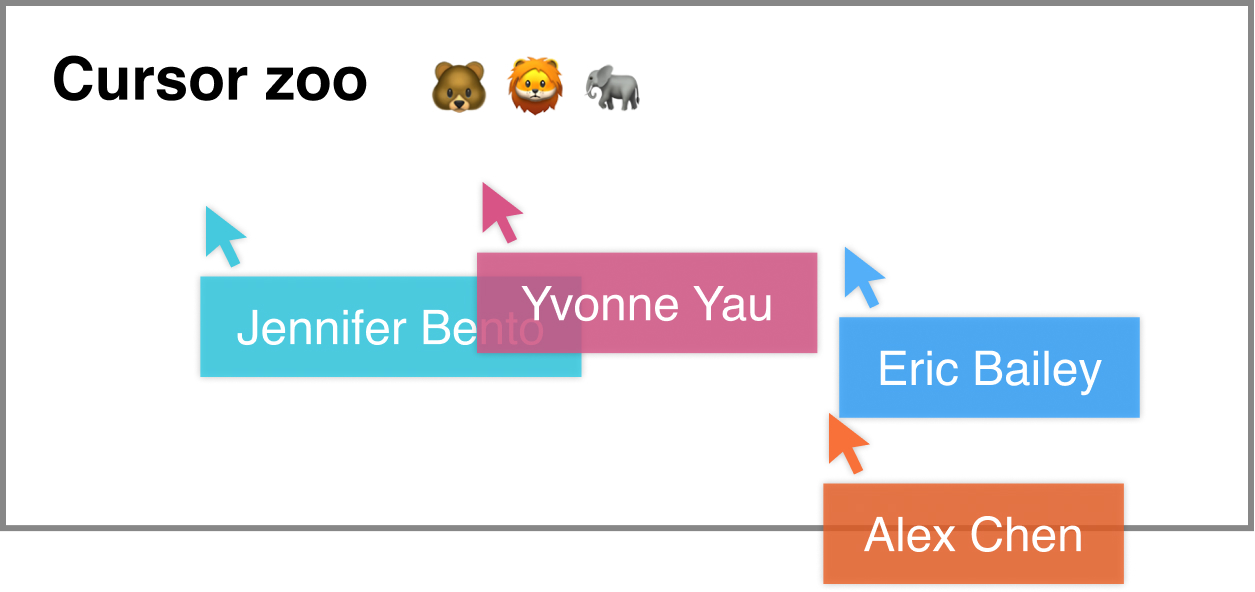

Make a cursor zoo

There are a lot of stopping points along an in-person sprint where a facilitator needs to give the team time and space to read and digest information. This is especially important on Converge Day, when reviewing others’ storyboards. Traditionally, folx will walk the room, and most likely take their seat when finished — a tacet indication that the team can move on to the next activity.

Replicating this social cue virtually was a stumbling block. Constantly asking the team if they were done is disruptive (this is meant to be a silent activity), ineffective (not everyone answers), and unscalable (imagine asking this to a room of 15 people instead of 7). Setting a timer puts unnecessary pressure on teammates who read and absorb new content at a different pace than others. That pressure is especially evident when power dynamics come into play (e.g. Not asking for more time to read because your boss is done reading).

Enter the cursor zoo. Or lobby. Or basement lounge. Whatever you want to call it.

Draw a rectangular area on your remote whiteboard. Tell participants to move their cursors to that designated zone when they’re done reading. Move on when all the cursors are present and accounted for. Voilà!

Share the wealth

Do you now feel completely prepared to shift your strategies and run your design sprints remotely?

You don’t?

Well, good. You shouldn’t. Much like design itself, the process of facilitating a sprint should be iterative and contextual to the product and the humans on your team. A lot of your best ideas may be totally off-the-cuff. It can be completely nerve wracking, which is normal (I am usually a puddle of nerves before each and every sprint I’ve facilitated.)

When running one, start documenting what’s working well for you and what’s not. And share that information! We’ll be a better design community for it.