Contributing to open source software can be scary. We all want to help sharpen our tools, but most of us don’t know where to start.

One of my favorite tools as of late has been Ember.js. Ember describes itself as

A framework for creating ambitious web applications.

Feeling a little ambitious myself, I decided to roll up my sleeves and get to work.

Getting the ball rolling

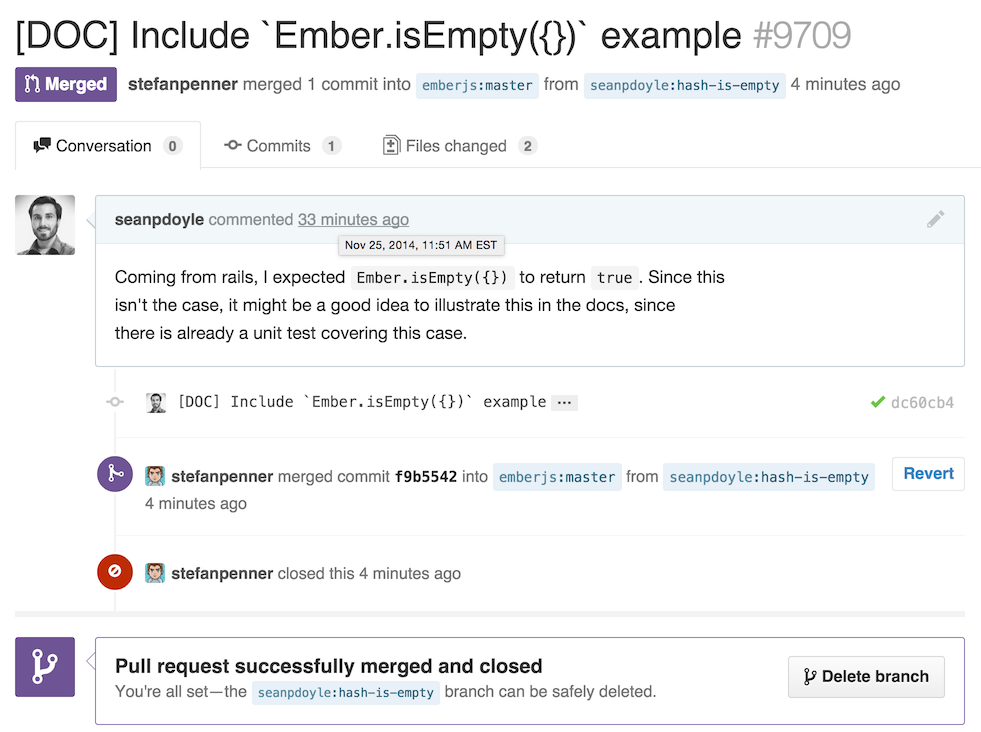

In the spirit of starting small, my first pull-request was a one-line fix.

Although the patch seemed inconsequential, the satisfaction I felt was not.

From my perspective, I now had my foot in the door. The thought of being a contributor to a framework that I use on a daily basis was gratifying, and left me wanting to contribute more.

Keeping the ball rolling

After my patch was merged, I searched through the contributors page for my name. Unsurprisingly, my tiny contribution hadn’t bumped me to the top of the list.

If I wanted to be ranked alongside the other highly esteemed contributors, I would have to have a more substantial impact. With my first contribution under my belt, I was excited to submit more ambitious patches.

Unlike my one-line documentation change, more substantial patches would require a deeper understanding of Ember and its package ecosystem.

My first reaction was to read through the random user-facing files in various

lib directories. This turned out to be ineffective, as I was quickly in over

my head.

I’m a strong believer that your test suite should serve as living

documentation, so I decided that I’d rather pick a package and

dive into its test suite. Since the framework was in the middle of its migration

from Handlebars to HTMLBars, I assumed the tests

covering the ember-htmlbars package would be the freshest, and thus most

interesting code.

Although my investigation was focussed on the ember-htmlbars test suite, its

dependencies on other packages drove me to familiarize myself with other parts

of the code.

While perusing the test suite, I took notice of code smells and submitted patches along the way. Some smells that I addressed included:

- missing test coverage (data#2513, data#2509)

- repeated setup & teardown (ember.js#9776)

- reaching into global state (ember.js#9778)

- copy-paste errors (ember.js#9781, ember.js#9775)

- general duplication (ember.js#9769, ember.js#9769)

This exercise was a big win.

Not only did refactoring the test suite force me to understand how the various components behaved both in isolation and in concert with one another, but improving the code along the way kept the process satisfying and fun.

I was even able to submit patches to user-facing code, first scratching my own itch (ember.js#9798), then scratching someone else’s (ember.js#9734).

Dealing with friction

Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on the code), your patches aren’t always merged.

As a first-time contributor, my biggest fear was that my code wouldn’t be good enough. I feared that I would be derided or feel belittled and rejected.

Lucky for me, this was not the case. Having your pull request rejected is something that is bound to happen. Sometimes, patches are too ambitious and lack a thorough understanding of how far the effects of their changes will ripple. Other times, patches are just a bad idea.

The important thing to take away from rejection is that a closed pull request isn’t the end of the world. As long as you learn something from the closed pull request, it was not a failure. Don’t let rejection discourage you from contributing in the future.

Conclusion

This is not the story of my meteoric rise to open-source super-stardom.

This is not the story of how I became an Ember core member overnight.

This is the story of how I mustered up the gumption to overcome my fears, uncertainties, and doubts about contributing to an open source project, and how you can do the same.

Start small, stay motivated, and keep patching.