This post was originally published on the New Bamboo blog, before New Bamboo joined thoughtbot in London.

When we build client-side applications, most of the problems we face are related to state management: what elements on screen need to be in sync with each other, how do we track changes locally and from the server, how do we effectively handle computed properties (like a user’s complete address when it’s composed by separate pieces of data).

What can we do to tame this complexity? In this post we’ll explore some ideas and lay out the basis for a unified strategy.

Defining state

It’s useful to remind ourselves what state is, as it goes way beyond the mere data that sits on our page.

Depending on the type of application we’re building, state can potentially be:

- The current url

- Dimensions of the window

- Mouse position

- Screen orientation

Not many applications need this level of granularity, but it’s important to remember that it’s possible to treat all of these dimensions as a form of state.

Identity and values

How can we frame the notion of state as something that changes over time?

We can get some help from the functional programming world, specifically from Clojure and its creator, Rich Hickey:

While some programs are merely large functions, e.g. compilers or theorem provers, many others are not - they are more like working models, and as such need to support what I’ll refer to in this discussion as identity. By identity I mean a stable logical entity associated with a series of different values over time. Models need identity for the same reasons humans need identity - to represent the world. How could it work if identities like ‘today’ or ‘America’ had to represent a single constant value for all time? Note that by identities I don’t mean names (I call my mother Mom, but you wouldn’t).

So, for this discussion, an identity is an entity that has a state, which is its value at a point in time. And a value is something that doesn’t change. 42 doesn’t change. June 29th 2008 doesn’t change. Points don’t move, dates don’t change, no matter what some bad class libraries may cause you to believe. Even aggregates are values. The set of my favorite foods doesn’t change, i.e. if I prefer different foods in the future, that will be a different set.

Identities are mental tools we use to superimpose continuity on a world which is constantly, functionally, creating new values of itself.

When we’re editing an article, its identity is stable, yet it can be represented by different values over time. All possible iterations of its content are values, all of them contribute to its history.

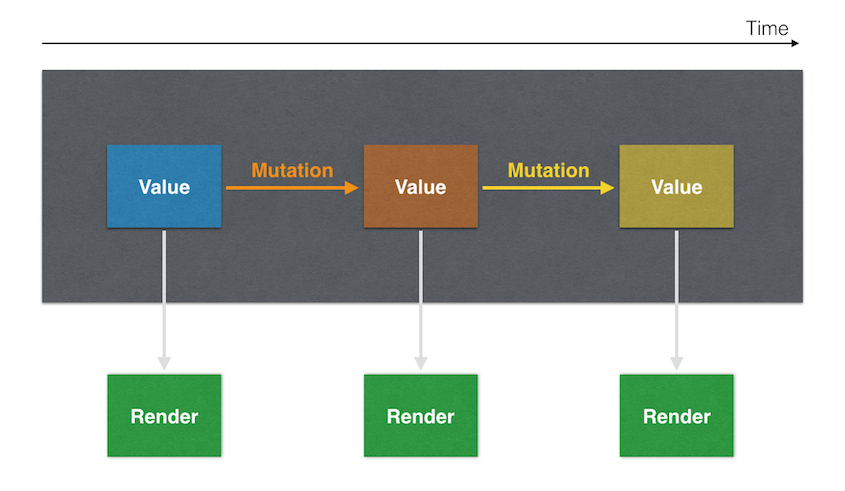

The direct consequence of this idea is that any application can be thought of as the succession of different values of the state over time. The transition between values is ruled by business logic and external input (e.g. user actions, data sources, etc).

Modeling mutations

Given this time-based notion of state, how can we model its mutations? Someone else to the rescue this time: John Carmack, one of the most important videogame programmers of all time with projects like Doom and Quake.

I settled on combining all forms of input into a single system event queue, similar to the windows message queue. My original intention was to just rigorously define where certain functions were called and cut down the number of required system entry points, but it turned out to have much stronger benefits.

With all events coming through one point (The return values from system calls, including the filesystem contents, are “hidden” inputs that I make no attempt at capturing, ), it was easy to set up a journalling system that recorded everything the game received. This is very different than demo recording, which just simulates a network level connection and lets time move at its own rate. Realtime applications have a number of unique development difficulties because of the interaction of time with inputs and outputs.

…

The key point: Journaling of time along with other inputs turns a realtime application into a batch process, with all the attendant benefits for quality control and debugging. These problems, and many more, just go away. With a full input trace, you can accurately restart the session and play back to any point (conditional breakpoint on a frame number), or let a session play back at an arbitrarily degraded speed, but cover exactly the same code paths..

I’m sure lots of people realize that immediately, but it only truly sunk in for me recently. In thinking back over the years, I can see myself feeling around the problem, implementing partial journaling of network packets, and included the “fixedtime” cvar to eliminate most timing reproducibility issues, but I never hit on the proper global solution. I had always associated journaling with turning an interactive application into a batch application, but I never considered the small modification necessary to make it applicable to a realtime application.

Carmack is talking about Quake 3 here, but the principles he’s outlining can be equally applied to the problem we’re handling.

- Collect all inputs into a single queue

- Process them and build a history of changes

The implications of this approach are more powerful than immediately apparent:

- If we transition from value to value over time, we can group all the logic that models these transitions in a single place. In other words, we can express all of the possible legal mutations to the state as actions with a semantic value: creating a new post, visiting the post page, fetching all posts from the server. Each one of them can be defined as simply as a function.

- The sequence of values for the state becomes the history of our application. Ideas like undo and redo suddenly become much simpler, as they just mean moving from value to value in opposite directions.

- By being careful around the way we shape our state values (what kind of data structures, the type of values we use and so on) we can get to the point where the state can be entirely serialized without any information loss. This means that we can potentially store it and retrieve it in the future.

Rendering

With all of this in mind, we can frame rendering as a visible representation of a state value, i.e. a certain value gets rendered in a specific way or, even more strictly, in only one possible way.

The application flow can then be described as:

- rendering of the initial state value

- collection of any input (location change, new data coming in, user action, etc.)

- state mutation and new value

- re-render

- repeat the process

This model is extremely simple, as it removes a lot of complications:

- a UI component is only responsible for collecting an input and calling a predefined action;

- the action will cause a state mutation;

- the application re-renders.

We can summarize all of this in this diagram:

A minimal example

In this example we’re creating a PostsList component, which takes some data and a DOM container and exposes a single render function. Every time the function is called, the component wipes out the contents of the container and renders a ul element with all titles.

How do we use it? We set its .data property and call render every time we want to update it.

Let’s make a small improvement, so that it re-renders every time we update the data.

Here we define a setData function that always calls render at the end. By doing this, we avoid calling render manually. In addition, we can use it straight away in the constructor function and get the first render automatically.

We can now proceed and implement a very rough state object and connect it to our component, so that we can manipulate a global state instead of the component state.

Our state object is a freeform store that allows registering callbacks when data change. This way we can register a callback for our component and every time we call appState.set it will fire and update the page.

The final thing we can do is flesh out an API to manipulate the state and give it some structure, using as an object as the underlying data structure.

All posts data is available under a posts key and we defined a clear Actions object that expresses the semantics of adding a new Post.

Performance and virtual DOM

There’s a caveat in this structure: re-rendering an entire application can be very expensive, as it implies rebuilding the entire DOM from scratch every time. Especially on mobile devices, this becomes a deal-breaker.

A few libraries (the most famous being React.js) are trying to mitigate this issue by providing a level of abstraction above the DOM, so that the developer can stop writing hand-coded DOM mutations and use a more declarative api.

The React lifecycle, for example, uses a conceptually simple approach: every render function creates a virtual DOM representation. The first time it gets rendered, it updates the DOM. When render is called again, React computes a new virtual DOM from the updated data and performs a diff against the previous one, calculating the list of fine-tuned mutations to apply to the DOM itself. For example, if the first time it would render a <h1>Title</h1> and the second time <h1>Updated title</h1>, it can just update the inner text of the element instead of destroying it.

In a nutshell, React embraces the rendering model we outlined above, giving us extra tools to tame the performance issue.

Where do we go from here

This post touches on many topics, each one of them worthy of further research on itself.

Here’s a list of resources that can be useful:

- The aforementioned links to Clojure’s documentation about state and John Carmack’s .plan entry about state management.

- The Elm architecture tutorial: we haven’t mentioned it before, but Elm is a very well designed reactive functional language that adheres completely to the architecture we’ve explored in this post. Many of its principles can be ported to JavaScript.

- Om’s architecture explanation. Om is a Clojurescript library that wraps React, with strong opinions about state management. Other suggestions may come from Reagent, another ClojureScript React wrapper.

- Ben Moseley, Peter Marks - Out of the Tar Pit: a good paper that explans in detail the implications of unnecessary stateful code.

- Guillermo Rauch - Pure UI: an exploration of how the React rendering model can ease the conversation between design and development.

Good lunchtime video talks:

- David Nolen - Immutability, interactivity & JavaScript: an exploration of the benefits of immutable data structures.

- The value of values with Rich Hickey: a great talk that explores ideas about the separation of logic and data and its implications.

- React.js Conf 2015 - Making your app fast with high-performance components: React specific, but it shows some principles around performant React applications that happen to be beneficial on architecture and simplicity as well.